The premise couldn’t be cleaner. A small desert town in Utah suddenly finds itself in the crosshairs of a demonic black car—no driver, no license plate, just an engine of pure malevolence. The only hope lies with a handful of lawmen and locals who, like Chief Brody and Quint in Jaws, must learn that their adversary isn’t just dangerous… it’s otherworldly. From the start, The Car borrows Spielberg’s slow-burn approach: the opening victims are a young couple out cycling. Instead of dorsal fins slicing through waves, we get the blaring, almost taunting blast of the Car’s horn—an unholy sound that quickly becomes the film’s death knell. The attack is merciless. The girl is scraped against a stone railing, while her boyfriend is sent tumbling off a bridge in a spectacular 196-foot plunge. It’s nasty, sudden, and very effective in setting the tone

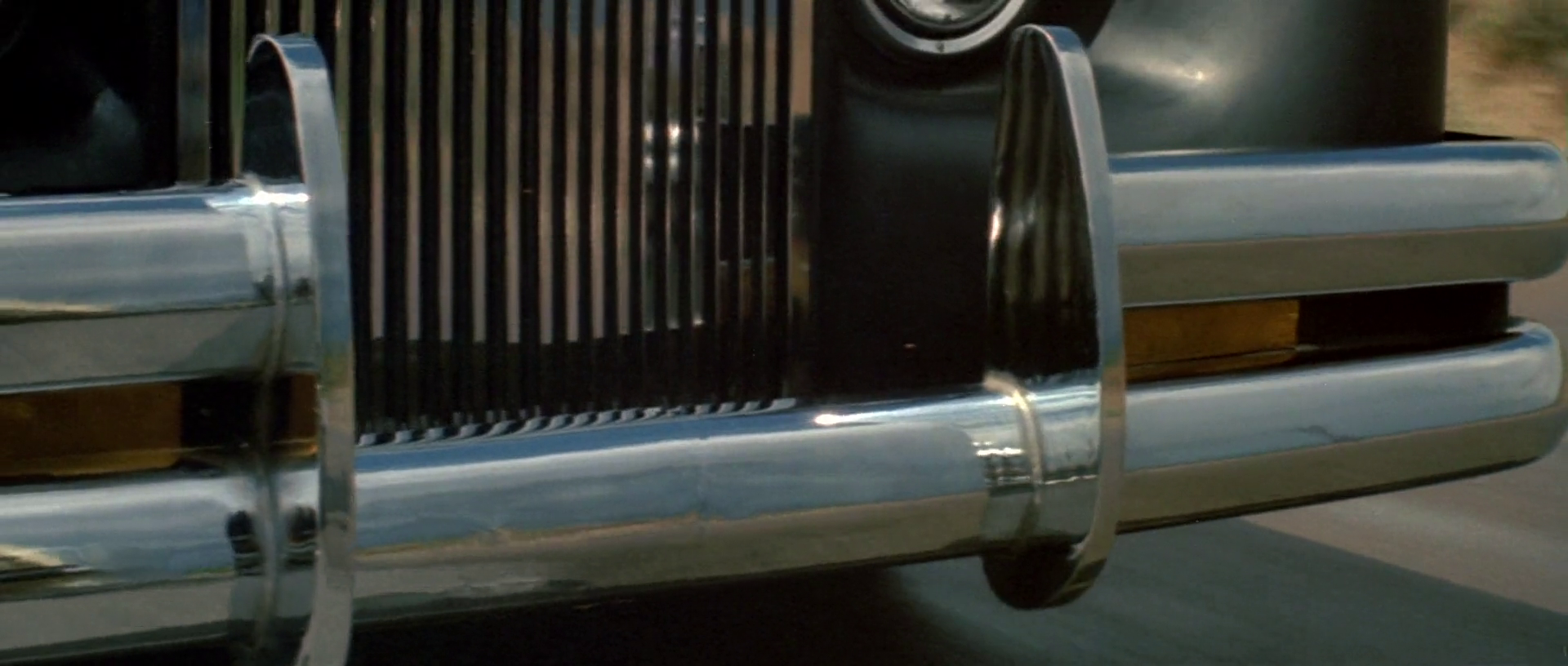

Behold the Grill of Death.

Behold the Grill of Death.

The next victim? A French horn-playing hitchhiker who flips off the Car after a near miss. Wrong move. The Car doubles back, runs him over repeatedly, and leaves him a crumpled warning to anyone who dares get in its way. This time, there’s a witness—Amos Clemmons (R.G. Armstrong), the local wife-beater, which puts the sheriff’s department on alert. The law here consists of Sheriff Everett Peck (John Marley), Chief Deputy Wade Parent (James Brolin)—a single father to two adorable daughters (real-life sisters Kim and Kyle Richards)—and Deputy Luke Johnson (Ronny Cox), a recovering alcoholic whose resolve isn’t strong enough to withstand the escalating carnage.

“So what are we thinking here, music hater?

“So what are we thinking here, music hater?

The first theory is simple: they’ve got a dangerous “crazy” on their hands. Sheriff Peck issues an APB, but the Car proves impossible to track… and soon claims Peck himself as a victim. Curiously, Wade notices something: the Car swerved to avoid hitting Amos Clemmons before targeting Peck, hinting at a bizarre moral code. And then there’s the testimony of an old Native American woman who swears there’s no driver inside. Naturally, nobody believes her—until it’s too late.

“Boss, never doubt old ladies, they know stuff.”

“Boss, never doubt old ladies, they know stuff.”

Sheriff Peck believes they have a “Crazy on our hands,” and has an all-points bulletin put out on the strange vehicle. Unfortunately for him, The Car doesn’t make itself easily tracked down, and the Sheriff finds himself becoming the next victim. What is interesting to Wade is that he saw The Car swerve to avoid the wife beating Amos Clemmons to then run down Sheriff Peck, so it seems The Car has an interesting moral code.

Doesn't pay to be a good man in this town.

Doesn't pay to be a good man in this town.

One of the film’s standout sequences comes when the Car crashes during marching band practice. Deputy Luke, having hit the bottle again, forgets to cancel the event as ordered. What follows is pure Jaws homage: a long tracking shot of the Car’s roofline gliding along a ridge, like a shark’s fin in the desert, before charging down toward the parade grounds in a choking cloud of dust. The schoolteacher, Lauren Humphries (Kathleen Lloyd), saves the kids by leading them into a cemetery, which the Car cannot enter. The unseen driver (or whatever it is) roars and circles the perimeter, but never crosses onto the hallowed ground. Later, Luke suggests the obvious: maybe it’s bound by supernatural rules.

"You're a chickenshit! Scum of the Earth, son of a bitch! "

"You're a chickenshit! Scum of the Earth, son of a bitch! "

From here, the confrontations escalate. The Car shrugs off bullets, crushes squad cars in spectacular stunt work, and even performs a gorgeous barrel roll over two police vehicles—one of the film’s signature action beats. In one tense moment, Wade empties his revolver at point-blank range into the windshield, only for the glass to remain unscathed. Then the door creaks open slightly, almost inviting him to look inside, before slamming him aside with a supernatural blast of force and vanishing in a flash of light.

"You have the right to remain parked!"

"You have the right to remain parked!"

Silverstein earns major horror credibility when Lauren, the romantic interest, is unceremoniously killed in the third act—mowed down without warning. It’s the film’s “everything just got real” moment, stripping away any illusion that anyone is safe. From then on, Wade and the surviving officers stop thinking of their adversary as just another killer; this is something far older and meaner. The plan? Lure the Car into the desert and bury it under tons of dynamite-triggered rockfall. The explosives, fittingly, are provided by Amos Clemmons—spared earlier by the Car, for reasons never explained.

Professional courtesy?

Professional courtesy?

The final showdown is gloriously absurd. Wade and Luke act as bait, standing exposed at the cliff’s edge until the Car charges them. At the last second, they leap aside, and the Car rockets over the cliff, right into Amos’s dynamite blast. For a moment, it seems destroyed… but Luke swears he saw a demonic face in the explosion. Nobody wants to believe him. Denial is easier—until the end credits, when we hear that familiar horn in Los Angeles.

The Devil is in the details.

The Devil is in the details.

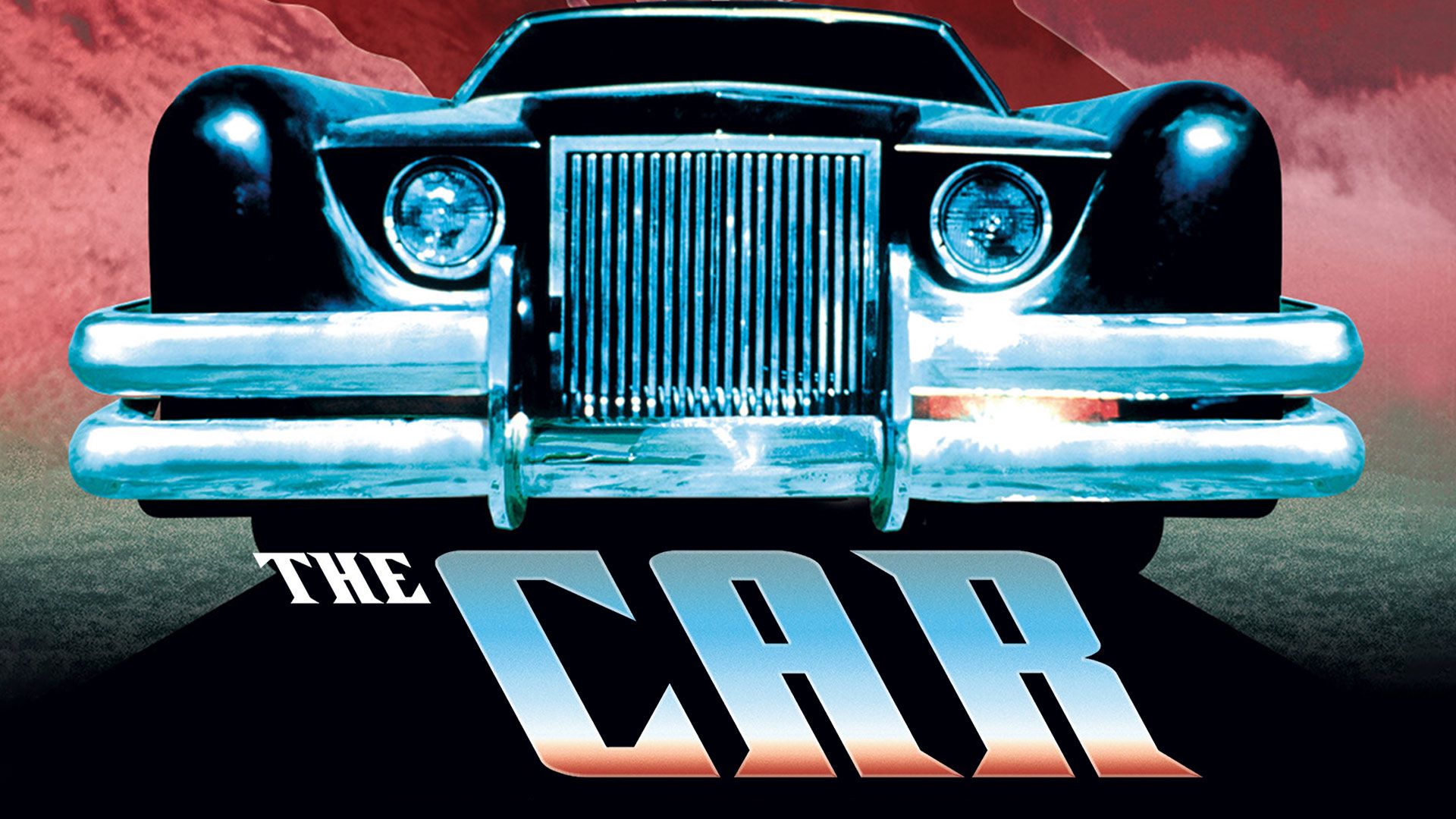

The cast does fine work grounding the ridiculousness. Brolin is especially good as a man forced from being a simple local cop into a supernatural warrior, while Cox brings quiet tragedy to the role of a man who knows he’s failing in his duty. Kathleen Lloyd is charming, and her abrupt removal from the story still shocks. Armstrong plays Amos with just the right amount of greasy menace. And one cannot overstate the importance of Leonard Rosenman’s eerie score. Its atonal brass stabs, combined with the Car’s guttural engine roar and hellish horn blasts, give the film an aural personality as distinct as Jaws’s two-note motif. Visually, the customized 1971 Lincoln Continental Mark III—designed by George Barris of Adam West Batmobile fame—is a work of sinister beauty: all low-slung menace, razor-thin windows, and matte-black intimidation.

Note: Those of you who haven’t had the privilege of seeing this film yet may have seen The Car when it appeared in an episode of Futurama that had Bender turning into a WereCar.

Want more proof that The Car is a movie worth checking out? Kenner designed a game for children at home to play, and what I gather from the description is that kids placed objects at the bottom of the ramp, and each spin of the wheel brought The Car closer until one object would finally trigger The Car's deadly run. Sadly, the objects are just stop signs, park benches and pylons and not hitchhikers or pretty school teachers. Even sadder is the fact that Kenner cancelled production plans, so this game never saw the toy store shelves.

I would have killed for this toy.

In the end, The Car may not have Spielberg’s craftsmanship, but it delivers a gloriously absurd, desert-set horror show where a honking demon on four wheels mows down anything in its path. It’s part Jaws, part Saturday matinee schlock—and all the more fun for it.

No comments:

Post a Comment