Along with Jules Verne, author H.G. Wells is considered by many to be one of the fathers of science fiction, but when looking at The War of the Worlds or The Time Machine it’s clear that though those stories fell under the umbrella of science fiction there were elements of horror as well, from the octopus-like creatures from Mars to the cannibalistic Morlocks the time traveller had to contend with, and thus it should be a surprise to no one that Universal Studios would turn to the works of H.G. Wells to provide more fodder for their growing horror line-up.

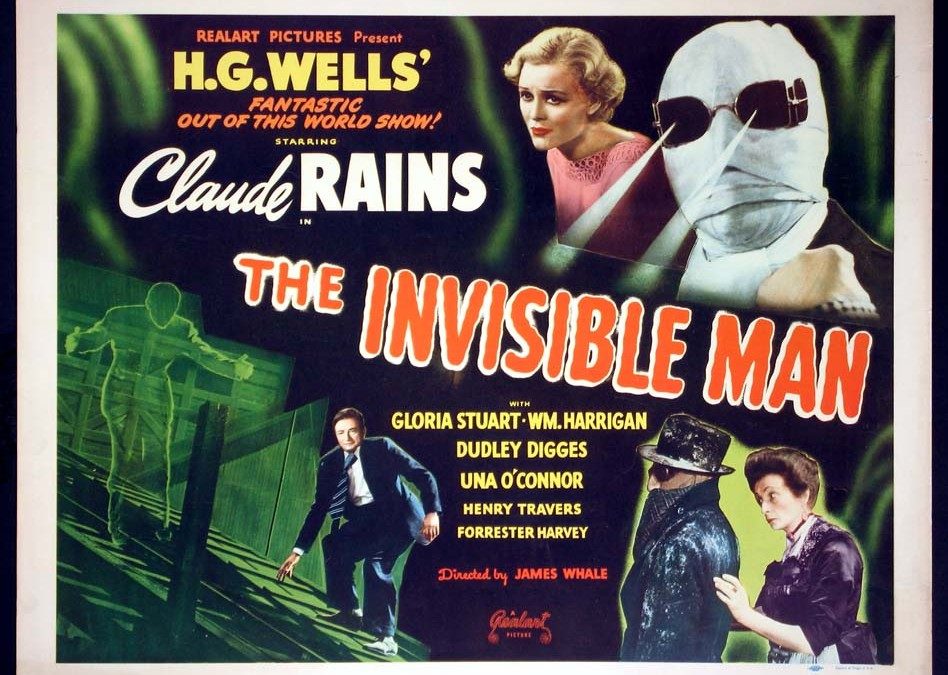

James Whale was once again tasked with bringing a literary classic to life and with his adaptation of H.G. Wells's novel The Invisible Man he was not only able to give the world a truly dark and terrifying villain but also a film with an equally dark sense of humour. Like the novel, the movie opens with a heavily clad stranger arriving at a village pub, his face hidden entirely by bandages except for a prosthetic nose, this man is scientist Dr. Jack Griffin (Claude Rains) whose experiments in invisibility have proved successful but have also set him a dark megalomaniacal path. In the book, Griffin’s madness stemmed more from the effect of being cut off from society, not that Griffin was all that stable an individual to begin with, but in the movie, his old boss Dr. Cranley (Henry Travers) reveals that the chemical monocane, a key ingredient to the invisibility formula, was later revealed in an experiment to have driven the subject mad.

Science Note: An invisible person would be completely blind as light would pass right through the retina without resistance, so unless your invisibility was based on a magic ring like in The Hobbit or the Cloak of invisibility in Harry Potter, don’t count on being able to see where you’re going.

One element that is quite visible in this movie, while also being quite absent in the novel, is the love interest of Griffin’s fiancée Flora Cranley, (Gloria Stuart), whose sole purpose seems to be in wringing her hands in distress about her missing fiancé. To quote Carl Denham from the 1933 production of King Kong, the reason for the inclusion of such a character is simple “Because the public, bless 'em, must have a pretty face” and it should be noted that the character of Flora is very similar to that of the fretting fiancée in Frankenstein, James Whale’s previous venture into horror, and this film also tosses in a rival suitor for some rather unnecessary romantic tension, in the form of Dr. Arthur Kemp (William Harrigan), of which a similar character also appeared in Frankenstein. In the book, Kemp was just a former acquaintance from medical school, who Griffin plans to enlist as a secret confederate in his mad plot, describing a plan to use his invisibility to terrorize the nation. While Kemp serves this purpose in the movie, as well as the forced love triangle, it is rather unnecessary and goes nowhere. In fact, Kemp lives in the book but is brutally murdered in the movie, so once Griffin is killed by the police poor Flora is left with no one.

Effects Note: The practical effects created by John P. Fulton to have objects float about as if being moved by an invisible man are quite impressive, unfortunately, optical effects were still in the early stages and thus scenes depicting empty shirts and pants dancing about were not always effective.

Aside from the very impressive practical effects developed by Fulton what really sells this movie is the performance of then-unknown actor Claude Rains, whose mesmerizing voice is so captivating that we get both a sense of manic madness as well as calculating evil in every dulcet tone, and for an actor whose onscreen performance, sans bandages, can be numbered in seconds, this performance is truly memorable. Speaking of memorable performances, James Whale was a director who loved to lace the darkness of his pictures with a liberal dose of comedy and in this film that came from a wide variety of character actors. most notable of these would be the innkeeper’s wife, played by Una O’Connor, whose shrieking hysterics I personally could have done without.

I’d rather poor Kemp had lived, and Griffin had killed her instead.

Stray Observations:

• Kemp states that “He meddled in things men should leave alone” which could practically be a bumper sticker for science fiction films of this period.

• I like that the village constable quickly realizes, “He’s invisible, that’s what’s the matter with him, if he gets the rest of his clothes off, we won’t catch him in a thousand years” which is a fairer depiction of law enforcement than what you usually get in these types of films.

• Griffin is killed because he leaves shoe prints in the snow, but that would have required him to find invisible shoes. We should have seen bare footprints in the snow.

• As monsters, Dracula and Frankenstein may have reached legendary iconic stature but as effective killers, they pale in comparison when put next to the Invisible Man, who in this film has a total body count of 122 victims. Even modern horror icons, like Jason Voorhees, would have a hard time matching that kill count.

“In your face, Krueger!”

James Whale’s The Invisible Man may not have had as great of an impact as the likes of Dracula or Frankenstein but when it came to the Golden Age of Horror, it did spawn a fair amount of good sequels and Claude Rains’ depiction of the ultimate murderous madman is still as chilling and gripping today as it was back in 1933, not to mention the fact that this film is still the most faithful adaptation of the H.G. Wells story to date.

No comments:

Post a Comment